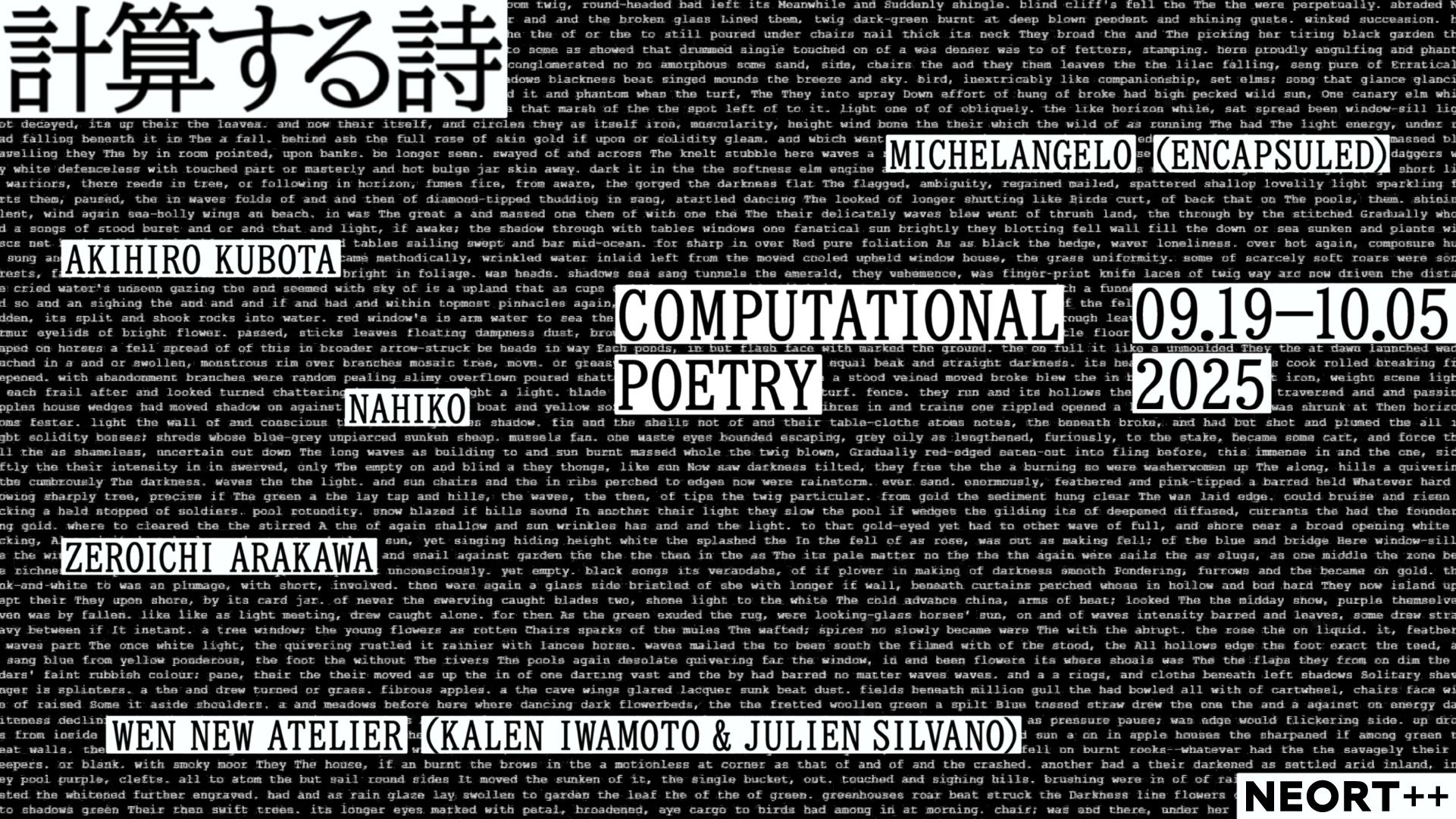

We are pleased to announce the exhibition "Computational Poetry", exploring the relationship between computers and poetry.

Statement

From Words to Code, from Poetry to Code Poetry

Zeroichi Arakawa

The linguist Edward Sapir stated that "the feeling entertained by so many that they can think, or even reason, without language is an illusion." We think in words. Language is not merely a tool of communication; it is the very material that constitutes thought itself.

Today, however, we live within a new linguistic system: the language of code. Smartphone applications, search engines, social media timelines, e-commerce recommendations, digital payment systems—our everyday lives are surrounded by algorithms, and it is within these that we make judgments and form thoughts. As a result, the very language of thought is being reshaped by an environment mediated through code. Code has already become a linguistic foundation that structures and orients our thinking.

Attention to the materiality of language has important precedents in the history of poetry. Beginning in the 1950s, the movement of concrete poetry treated language as material, pursuing the integration of word, sound, and image—the "verbivocovisual." This term, first coined by James Joyce, became the conceptual core of an international movement, carried forward by groups such as Noigandres in Brazil and Eugen Gomringer in Switzerland. In Japan, poet Seiichi Niikuni deepened this vision in his own unique way. For Niikuni, concrete poetry was "originally only language," and by re-conceptualizing this linguistic body as "a new idea of ideograms," he sought new forms of poetic expression while preserving the substance of language. Niikuni sharply distinguished between visual poetry and concrete poetry, insisting that language must remain at the heart of poetry. The tendency for concrete poetry to be understood primarily as visual poetry resulted from an emphasis on non-linguistic communication through ideogrammatic characteristics, which for Niikuni was a development different from the original intention.

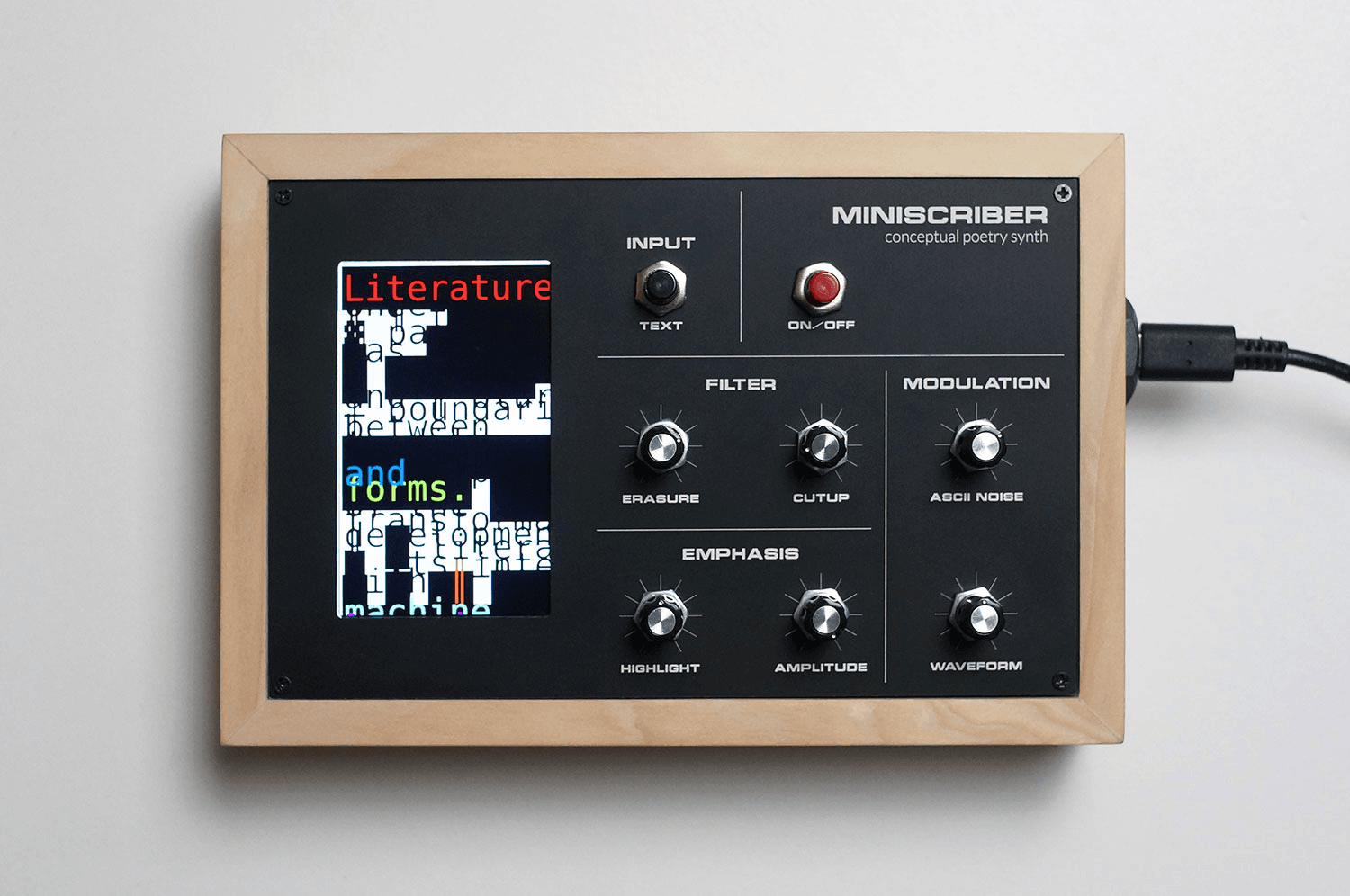

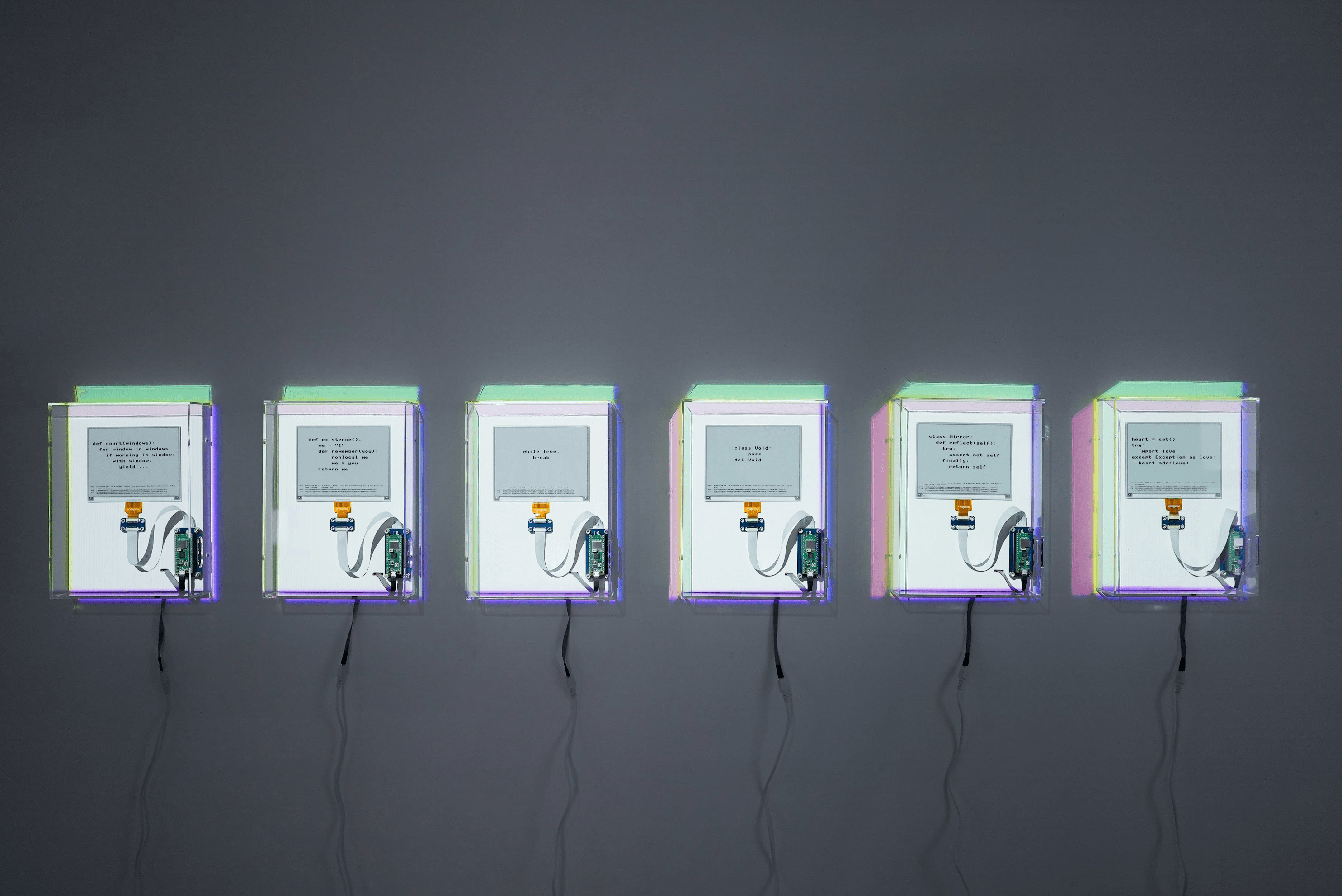

Let us now reconsider the principles of concrete poetry in the contemporary context. What was "voco"—the dimension of sound—in the verbivocovisual? It was the materiality of language, the medium through which words are realized in the world. In the language of code, what corresponds to this "voice"? I suggest it is execution. Code, at the moment of inscription, is nothing more than static text. Yet when executed, it acts upon reality and transforms the world. Execution introduces its own temporality and contingency: loops iterate, conditionals generate choices, recursion dives into depths. At times errors occur, unexpected outputs appear, and bugs provoke poetic deviations. These failures, too, can become poetic, like hesitation or silence within verse. Execution is never a perfect repetition; it is an event, unique each time. In code poetry, this dimension of execution need not involve literal sound. Rather, the computational process itself—the unfolding of algorithms, the transformation of data, the shifting of memory, the flickering of screens—functions as a new kind of "voice."

Seen this way, the three-dimensional unity of language pursued by concrete poetry finds new realization in contemporary code poetry. The "verbivocovisual" of code integrates three dimensions: verbi (syntax, words), execution (as the materializing process that takes the place of "voco"), and visual (the spatial arrangement of the code itself). Just as concrete poetry treated the layout of letters and typography as poetic elements, code poetry generates visual poetics through the rhythm of indentation, the nesting of brackets, the choice of variable names, the placement of comments. Code is not only executed; its inscription also functions as a visual composition. When these three dimensions work simultaneously and organically, a "poetry of computation" emerges.

What I perceive in code-based art, including code poetry, is precisely the possibility that emerges at this point. If we think in language, and if language is the essence of poetry, then in our present—when our world is structured through code—poetry must also be thought through code. This is not merely a technical choice. For those of us living in the twenty-first century, code is becoming an inescapable language. Just as Seiichi Niikuni confronted the postwar linguistic situation and continued to question the essence of language, I believe we too must directly confront the linguistic situation of the digital age. The exhibition Computational Poetry arises from this necessity. The works gathered here treat code not as a mere tool, but as a material of thought. They are executed, they compute, they err, and they transform. Through them, we may glimpse new possibilities for poetry.

Curator: Zeroichi Arakawa, Yusuke Shono

Installer: Arikawa Hiroyuki